Introduction to NAT and Internet Growth

The internet began as a small research idea and then grew into a global system that links billions of devices, and each device needs an IP address so it can send requests and get answers. At first there were enough IPv4 addresses to hand out, but the pool kept shrinking as more people and more machines came online year after year, so engineers looked for a way to stretch what was left. That search led to methods that make one public address serve many private devices, and one of the most used methods is Network Address Translation, which most people just call NAT.

NAT lets many devices inside one home or office or school share a single public address when they talk to the wider internet, and the router does the translating work quietly. A family with several phones and laptops and a smart TV can all be online at the same time through that one public identity, and the same idea holds in larger networks that need to keep growing without burning through public space too fast. It was not made as a perfect or permanent fix, but it became a key piece that holds things together while the move to IPv6 goes on slowly, and it keeps daily connections smooth enough so apps keep working and services stay reachable.

Understanding the Basics of NAT

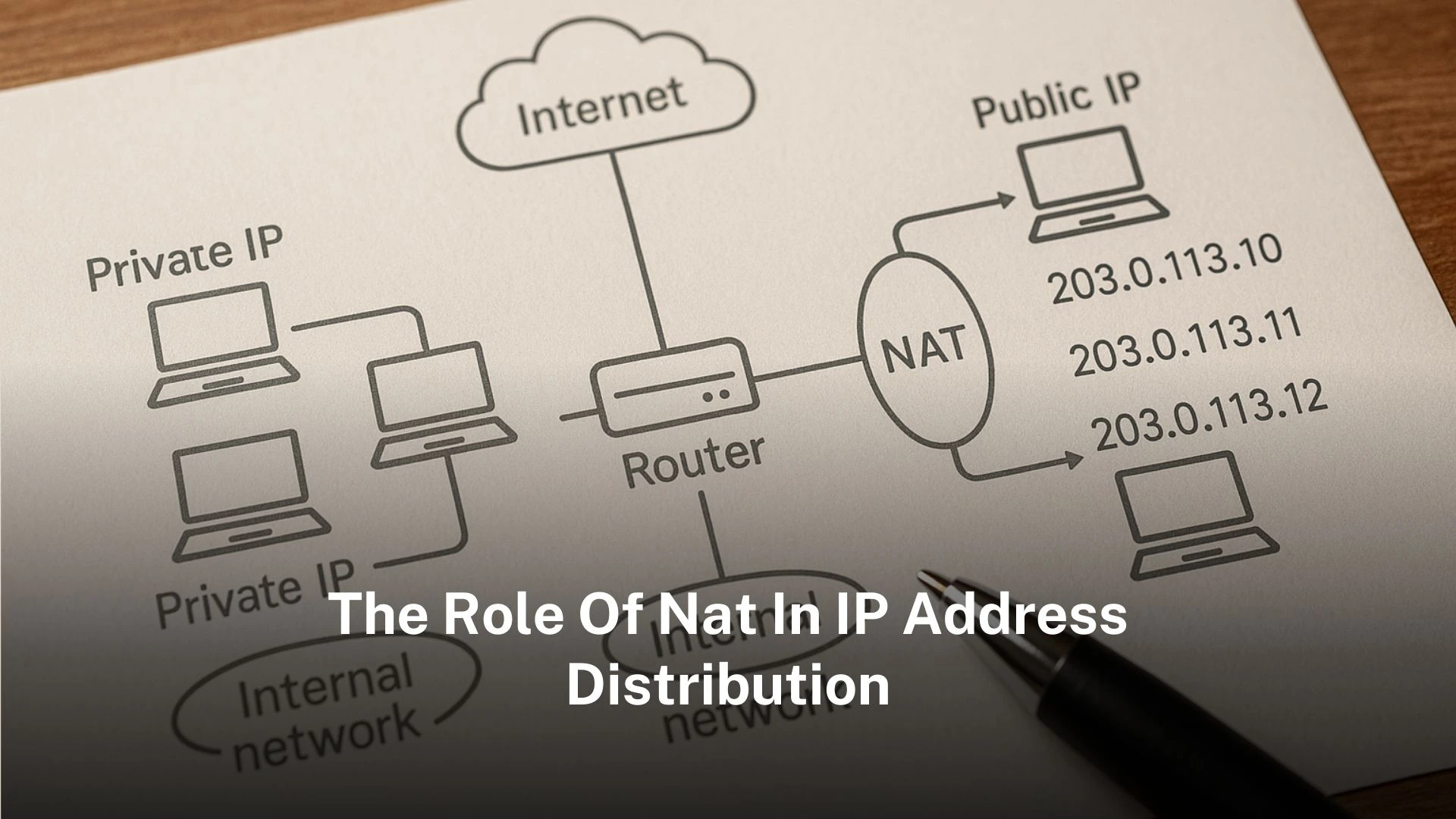

The idea behind NAT sounds simple and the busy part sits inside the router, because a device on the local network sends a packet with a private address and the router swaps that source for the shared public address before it leaves. When the reply comes back from the server, the router checks the table it keeps and knows which private device asked for it, so the data finds the right place again and the user only sees that pages load and videos play.

The form most people use is Port Address Translation, or PAT, which gives each connection its own port number so one public address can cover many private devices at once and still keep the traffic sorted. In a house that might mean streaming and gaming and browsing at the same time, and outside observers still see only one public IP, and the router matches ports to devices so sessions do not get mixed. There are other forms too, like static NAT that maps one private to one public when a server inside needs to be reached from outside, and dynamic NAT that hands out public addresses from a pool as needed, and each form tries to use scarce space more carefully while keeping networks flexible.

Because NAT hides the layout of the private network, strangers on the internet cannot see the devices inside directly, and that adds a thin layer of separation that feels like basic protection even though it is not a full security tool. This mix of saving public space and keeping a little distance from the outside explains why NAT became common and why almost every consumer router ships with it ready to use, and that is how it ended up in the middle of daily internet life.

The Problem of IPv4 Scarcity

IPv4 gives about 4.3 billion unique addresses, and in the early years that number looked more than enough. Large organisations, universities, and government networks were handed big blocks, sometimes bigger than they could ever use, because at the time nobody thought addresses would run out. But the internet kept spreading and more people wanted to be online, so addresses that once seemed endless began to look limited, and then the pool started to shrink much faster.

The spread of smartphones turned the slow drain into a rush, since people who already had a computer at home also wanted their phones and tablets and smart TVs to stay connected all the time. Each device asked for an IP, and the available space could not keep up. By the early 2010s most regional registries were saying openly that they had no fresh IPv4 left to give, and new requests had to be handled differently.

If NAT had not been in place, the shortage would have hit much earlier and in a harsher way. Homes and offices would have needed several public addresses each, and providers would not have been able to satisfy the demand. NAT let those homes and businesses use private ranges inside and then share one or a few public addresses outside, so the same space served many more users than before.

NAT does not end scarcity but it slows down the damage. ISPs can connect more households without rushing to buy large blocks on the market, and users can keep adding new gadgets without asking for a new subscription each time. For most people this made the shortage invisible. They just carried on using the internet while NAT quietly extended the life of IPv4 and gave the industry more time to move slowly toward IPv6.

How NAT Mechanisms Work in Practice

NAT runs in the background so most people never notice it working. A laptop asks for a webpage, and the packet goes out carrying a private source address. The router swaps that for the shared public one before sending it to the internet. When the answer comes back, the router checks its table, knows which private device requested it, and sends the reply to the right machine. To the user this looks like a simple page load, but inside the router a constant stream of translations is taking place.

The kind of NAT that shows up most is Port Address Translation or PAT. Here, a single public address can cover hundreds of private devices, with each connection getting a different port number. A family can all be online at once, watching movies and playing games, yet outside only one public IP is visible. The router tracks which port belongs to which device and keeps everything sorted. Static NAT, which links one private address to one public address, is used when a server inside needs to be reached from outside. Dynamic NAT, which hands out public addresses from a pool when needed, still has uses in enterprise setups. Each form tries to make the pool last longer and keep things flexible.

NAT adds other side effects as well. Because it hides the internal structure of the network, outsiders cannot see each device directly. This was not the main design goal, but it gave a thin extra layer of separation. It does not replace a firewall, but it lowers visibility from the outside. At the same time, NAT can block some direct services. Online games, peer-to-peer software, and video calls may have trouble crossing NAT without helpers like STUN or TURN servers. Carrier-grade NAT, which many providers use, saves even more addresses but makes life harder for customers who want to host servers or connect directly.

NAT’s Role in IP Address Distribution

NAT does not replace the role of registries or allocation policies, but it changes how addresses get used in practice. In theory, every device should have its own public address. In reality, NAT lets millions of private devices sit behind one or a few public addresses. This stretches the pool much further than direct one-to-one mapping ever could.

Service providers use NAT heavily to keep signing up new customers even after their address blocks are nearly full. A single ISP can cover thousands of households with a small set of public addresses. Each customer has a router doing translations, and many providers add another layer of NAT in their core. This stacking of NAT systems is what allowed the internet to keep growing even after the free IPv4 pool was gone.

For users, NAT makes scarcity almost invisible. At home, they can plug in more devices without asking for new addresses from the provider. At schools and offices, hundreds of computers can connect through one public IP. In both cases, NAT is the reason access can be distributed more widely without waiting for fresh allocations. Without NAT, many users would already have been cut off years ago.

NAT was always supposed to be temporary, but slow IPv6 adoption turned it into a long-term part of the system. It is now central to how providers manage addresses, how companies design their networks, and how ordinary people get online every day. Even though IPv6 was meant to replace it, NAT still sits in the middle of distribution today.

Challenges and Limitations of NAT

While NAT has kept IPv4 usable, it also breaks some of the internet’s original ideas. The early design allowed any device to talk to any other directly. With NAT in place, devices inside cannot be reached from outside unless extra settings are made. This makes it harder for people to run servers at home. A person who wants to host a game or a small site often has to use port forwarding so outside traffic reaches the right device.

Peer-to-peer applications face the same problem. They need direct paths, but NAT blocks them by default. Developers have created tricks to bypass this, but those workarounds add complexity and sometimes slow things down.

Carrier-grade NAT goes further by placing hundreds of customers behind one shared address. This saves space but limits what users can do. Hosting servers, using remote access, or tracking abuse becomes harder because many people share the same public IP. Providers then must keep logs of which private user matched which port at each time. That adds cost and technical load.

Impacts on Businesses and Everyday Users

For companies, NAT made growth possible without huge costs. A firm can run many devices with just a few public IPs. This avoids spending money on the transfer market and lets the business expand more freely. Smaller ISPs rely on carrier-grade NAT to add customers without waiting for new allocations, which helps keep services alive even when registries have nothing left to hand out.

For home users, NAT is nearly invisible but still central. It means one subscription can cover phones, laptops, and smart devices together. Schools and offices use the same idea on a bigger scale. The router handles the busy work of translation so that people never have to think about addresses at all. NAT is the quiet reason they can enjoy a smooth online experience.

NAT and the Transition to IPv6

IPv6 was designed to remove the problem by offering a pool so large that every device could once again have its own public address. If IPv6 were fully deployed, NAT would not be needed anymore for conservation, and the internet could return to its original end-to-end style.

But IPv6 adoption has been slow. Many networks still run mostly on IPv4, and many services still expect IPv4 connections. Providers now run dual-stack setups, but as long as IPv4 is in use, NAT has to stay. The long transition has turned NAT from a temporary trick into a permanent tool.

NAT also complicates the move to IPv6. Some providers, used to relying on NAT, put off upgrades to their systems. Others build hybrids that mix IPv6 with NAT. These solutions keep things working for now but slow the full shift. In this way NAT is both helpful and harmful. It makes IPv4 last longer, but it delays the full change to IPv6.

FAQs

1. What is the role of NAT in IP address distribution?

NAT’s job is to let lots of private devices sit behind just one public IP when they go online. This way the same small pool of addresses can serve many more people. It does not remove the shortage, but it slows it down and makes the existing space last longer.

2. Why has NAT become so important in modern networks?

The simple reason is that IPv4 space is gone while demand keeps climbing. NAT gives providers a way to keep adding new customers and lets households keep plugging in new devices without asking for extra public space every time. Without it, the internet would have hit a wall years earlier.

3. Does NAT provide security benefits?

In a way it does, because it hides the inside of a network from the outside world. People scanning the internet do not see every private machine, only the public face. But that is just a side effect. It is not a full defence, so you still need firewalls and other tools.

4. What are some of the problems with NAT?

The biggest issue is that it blocks direct paths. Peer-to-peer tools, games, and calls often struggle, and home servers need special setup to work. On top of that, providers must keep more logs to trace activity, which means extra cost and complexity.

5. Will NAT still be needed when IPv6 is fully adopted?

If IPv6 is everywhere, NAT will not be needed for conservation, because each device will have its own unique public IP. Until that point, NAT will remain part of the system, since IPv4 still underpins much of the internet.

Some genuinely nice and useful info on this website , too I believe the design contains great features.